From Weddings to Riots, Everything to Know About Eggnog’s History

It’s that time of year again, when streets are lined with twinkling lights and supermarket shelves are stacked with brightly decorated cartons of eggnog. How eggnog landed on supermarket shelves, synonymous with the winter holidays, is a story as rich as the creamy, spiced, egg-laden drink itself. While eggnog’s roots are in Europe, American history is to thank for the drink we know and love today.

Eggnog’s Early Origins

The origin of eggnog is difficult to pinpoint, but most culinary historians believe its earliest traceable relative is a hot and heady concoction called posset, which was imbibed in early modern Britain. Sasha Handley, a professor of early modern history at The University of Manchester, writes that posset had medicinal uses and was also the “culinary pinnacle of 17th-century wedding celebrations,” enjoyed by bride, groom and wedding guests to cement the bonds of a new marriage.

At an early modern English wedding, the bride’s family might prepare posset using heated milk or cream, spices like cinnamon or nutmeg and various alcohols, most often ale or a sweetened white wine called sack.

Eggnog in Early America

The English’s beloved posset and the traditions surrounding it traveled across the Atlantic with settlers in the 17th century. Intricately-designed pots dating to the mid-17th and early-18th centuries designed for serving posset have been discovered at archeological dig sites in New England. But while the drinkware may have endured for a time, traditions and recipes quickly changed in the New World. On North American soil, settlers adapted old recipes to utilize the abundance of colonial-era farms, where milk and eggs were plentiful.

“It originated in the household as a way of preserving food,” says Clinton Lanier, author of the forthcoming book Ted Mack and America’s First Black-Owned Brewery. When eggs and dairy neared the end of their shelf life, in an era before widespread refrigeration, mixing them with sugar and alcohol kept them from spoiling. Lanier says the drink would have also been available all year long at inns or taverns throughout the colonies. Most historians agree it was also during this period that eggnog got its name—a mixture of the words “egg” and “grog,” the latter a term American colonists used for rum or sometimes other alcohol.

Rum and sugar’s presence in eggnog, however, can be traced to an ugly piece of American history. Whereas posset called for wine or ale, rum was more readily available and affordable in the New World—the result of the Triangle Trade, which saw enslaved Africans forced to grow the sugar that was used to brew rum. As a result, rum and sugar were used in most early eggnog recipes in America, according to Lanier. And unlike posset, eggnog was affordable enough on American soil to become an everyman’s indulgence.

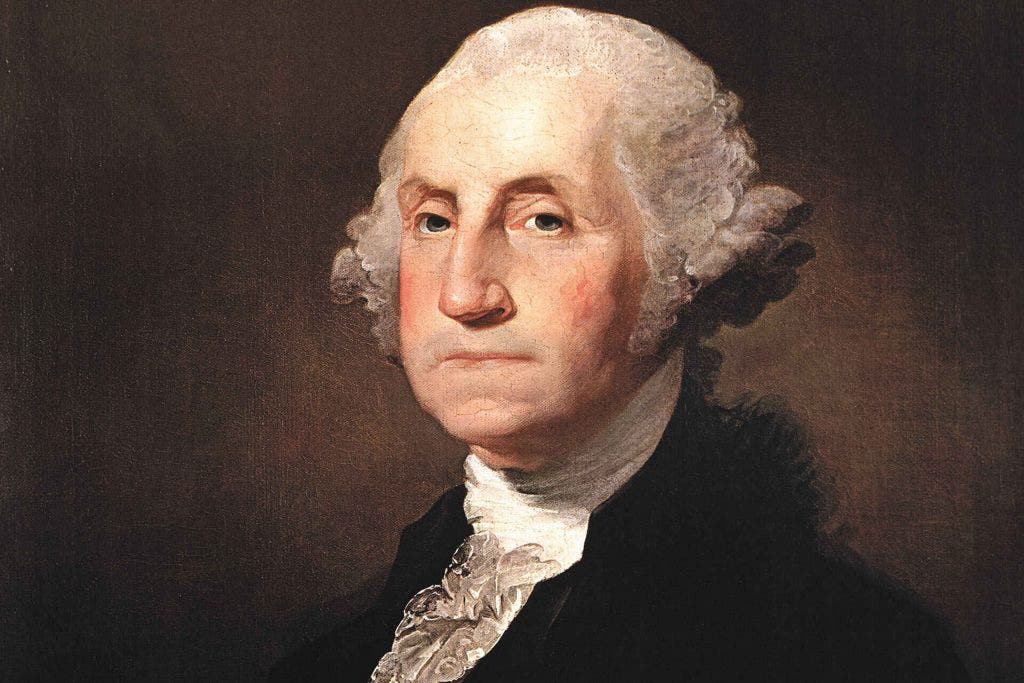

While the average person would have spiked their eggnog with rum, Lanier says more affluent families used other liquors or a mix of several. “A lot of the recipes from the period published in books would suggest a mixture of different liquors, giving the eggnog different tastes,” he explains. Perhaps the most famous historical eggnog recipe is George Washington’s, which called for brandy, rye whiskey, Jamaica rum and sherry alongside cream, milk and a dozen heaping spoonfuls of sugar.

Once some version of eggnog had made its way into American homes, different regions developed their own recipes and traditions.

It also stirred up several conflicts and flavored various celebrations throughout the 19th century.

The Eggnog Riots

No eggnog-related conflict is more famous than the riot at West Point Military Academy in New York in December 1826. The academy’s superintendent had forbidden the purchase, storage or consumption of alcohol on school premises earlier that year. But when Christmas time came, cadets were fed up with sobriety and intent on celebrating, so they smuggled in gallons of whiskey and whipped up a batch of eggnog to enjoy on Christmas Eve.

A superintendent caught a couple of inebriated cadets partying together in the early hours of Christmas morning and ordered them to disperse and sober up. They responded instead by gathering their friends and launching into several hours of eggnog-fueled holiday chaos and destruction—now known as the eggnog riot.

One of the cadets was Jefferson Davis, who would go on to lead the Confederate States as their president during the American Civil War. After his armies lost to the Union in 1865, revelers in southern cities celebrated Christmas with rivers of eggnog.

A newspaper clipping from Petersburg, Virginia, where residents had spent the preceding Christmas under siege, describes “numberless rows” of people who had drunk enough eggnog before breakfast on Christmas morning “to put everybody in a good humor.”

When the Temperance Movement picked up steam in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, eggnog and other holiday liquors became a high-profile target. Temperance activists condemned the tradition of barrooms serving free or cheap eggnog on Christmas in quantities enough to keep merrymakers drunk all day.

Eggnog and Today’s Christmas Connection

Through it all, eggnog endured. Although these days, the drink you find at the supermarket or order with your holiday-themed latte looks little like the one that egged on riots at West Point or drew the ire of temperance activists.

The major differences? The addition of spices, preservatives, stabilizers and the absence of alcohol, says Lanier. Of course, you can always add bourbon, rum, or whiskey to zero-proof, store-bought versions at home. Some brands have also started to sell pre-mixed, alcohol-packed eggnogs that Lanier says are “closer to the real thing.”

Regardless, one thing is clear about modern-day ‘nog: This drink is synonymous with Christmas.

But its relegation to Christmastime is a modern turn. As refrigeration became more widely available and the country became more industrial and less agrarian in the early 20th century, there was less need to use eggnog for preservation.

“The drink became more nostalgic and sentimental,” says Lanier. “Eggnog became the drink associated with the holiday season.”

Today, manufacturers could make the drink all year—but they don’t. It simply doesn’t sell very well in the spring or summer. However, come autumn, producers see a major uptick in sales and demand for eggnog.

After all, what would Christmas be without the creamy stuff? Lucky for us, there are plenty variations from which to choose. Whether you’re into long-aged Creole egg nog or classic hot eggnog, coconut milk-spiked coquito or egg-free vegan nog, there’s a little something for everyone.